Published September 11, 2018

This Is What Conservation Looks Like

Heads up! This article was published 6 years ago.

con·ser·va·tion (noun)

känsərˈvāSH(ə)n/

- The action of conserving something, in particular:

- preservation, protection or restoration of the natural environment, natural ecosystems, vegetation and wildlife.

- preservation, repair and prevention of deterioration of archaeological, historical and cultural sites and artifacts.

- Conservation is the science-based philosophy and inspiration that guides the long-term management and protection of the nearly 16,000 acres of natural areas Five Rivers MetroParks manages.

Conservation is the reason for Five Rivers MetroParks.

More than 50 years ago, a group of citizens realized suburban development was flying at a fast clip, but the Dayton region had no process to preserve open space to protect water, provide habitat for wildlife, and support human health and recreation. They worked to create a park district that today is your Five Rivers MetroParks.

These citizens also knew parks and open spaces are a piece of the economic development puzzle and must be protected. That still holds true: A June 2018 report commissioned by the National Recreation and Park Association found parks and recreation agencies contribute to the economic development process through business attraction, retention and expansion by improving regional quality of life. Today, your MetroParks protects nearly 16,000 acres of parks, greenways and waterways and is proud to help provide a high quality of life for people throughout Montgomery County.

But MetroParks does much more than prevent that land from being bulldozed. Staff use best practices in the science of conservation to manage that land. Just as you might mow your lawn and weed your garden beds to keep everything growing where you’d like it to in your yard, MetroParks parks and conservation staff manage the land the agency protects to ensure it includes habitat for a variety of wildlife — and places for people to enjoy nature, too.

MetroParks’ conservation and land management practices have evolved through the years with advances in science and with steady growth in the number of acres MetroParks manages.

In the park district’s early years, people believed a hands-off approach would allow the process of natural succession to, with time, convert former farmland to its prior state. However, biological surveys revealed that, without land management, that former farmland would eventually be only forest — and not necessarily a high-quality forest at that, thanks to a variety of factors. Those include the introduction of harmful invasive species, such as honeysuckle and the emerald ash borer, and overpopulation of large wildlife, such as deer, that no longer have natural predators.

“In the ’80s, MetroParks staff realized we couldn’t just buy land and let nature take its course,” said Mary Klunk, regional conservation manager. “We needed to take a more proactive approach and be land stewards, actively creating habitats like prairies, edge thicket and wetlands.”

Creating those habitats leads to biodiversity, which means wildlife from the tiniest microbes to the largest deer have places to live and things to eat. It means the cycle of life so critical in nature takes place in your MetroParks.

Being land stewards leads to a community approach, which means all MetroParks staff work with volunteers, partner organizations, schools and universities, and countless others toward the long-term protection of nature. It means working with other property owners to protect and manage corridors of land, many of them along the region’s waterways, to provide large tracts of land where such wildlife as coyotes and bobcats can find homes.

And being proactive means taking a bird’s eye view of the land in Montgomery County as if it were a puzzle.

“At one time, nature had had all the puzzle pieces and succession would happen naturally,” Klunk said. “Our job is to keep identifying which pieces have been lost and figure out how to replace them.”

Yesterday and today, conservation is at the heart of everything Five Rivers MetroParks does and is in every employee’s job description. Conservation at your MetroParks looks like everything from staff building a new wetland on former farmland to throwing their banana peels in a compost bin.

“Conservation will continue to be central to Five Rivers MetroParks’ mission,” said Chris Pion, director of parks and conservation. “Protection and preservation of natural areas rated highly in recent community feedback that was received as part of the comprehensive master plan.

“Access to nature has documented health benefits, especially for children,” he added. “Due to the protected network of parks and conservation areas, residents have the opportunity to learn about and experience an amazing amount of biodiversity close to home.”

When you get out and explore your MetroParks this fall and winter, look for conservation in action. It may be as simple as a sign asking you to recycle or reuse park brochures. Or perhaps you’ll come across one of the projects mentioned below in this history of Five Rivers MetroParks’ conservation efforts, which also includes efforts happening now or planned for the future.

“MetroParks provides places where people of all generations can be connected to each other and to nature while learning about our community’s natural heritage,” Klunk said. “These old forests are spiritual places. If those forests are cut down, we can’t replace them in our lifetime. Kids need to have those places to see and explore. We have to be able to continue to provide forests and prairies and wetlands — special places where people can experience and connect with the natural world.

“Think about some of your favorite moments,” she added. “How many of them include nature? How many of them took place in a MetroPark?”

CONSERVATION HISTORY IN YOUR FIVE RIVERS METROPARKS

1959

1959

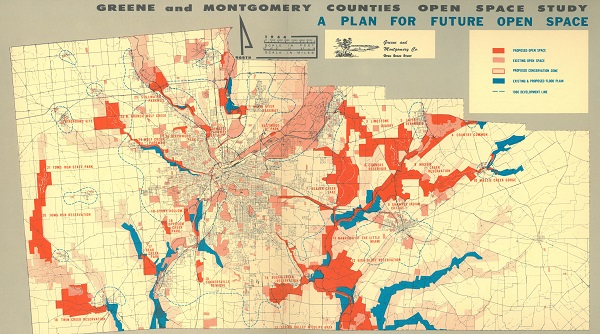

A study of the effects of urban sprawl and dwindling open space in Montgomery and Greene counties led to the formation of the Save Open Space Committee. Its members decided forming a park district was the best way to fulfill the community’s needs for open space.

1963

The Montgomery County Park District was created “to protect natural areas, parks and river corridors, and to promote the conservation and use of these lands and waterways for the ongoing benefit of the people in the region.”

1965

THEN: The park district set a land acquisition goal of 8,500 acres (one acre for each 1,000 residents) and established a policy to maintain 80 percent of park lands in a natural state, with the remaining 20 percent to be developed for picnic areas, trails, shelters, parking lots, etc. The district also created a master plan for park locations to serve all of Montgomery County. Land acquisition began in those areas where potential development was the greatest. Drylick Run, now Carriage Hill MetroPark, was the first to be acquired.

NOW: Five Rivers MetroParks maintains nearly 16,000 acres of land — 90 percent of it preserved as natural area. This habitat has contributed to the rebound of several native wildlife species, including river otters, bobcat and bald eagles. The land is home to 18 clean, safe MetroParks, and most Montgomery County residents live just minutes from a MetroParks location.

1966

THEN: The park district purchased 275 acres to create Possum Creek MetroPark; much of the land had been used as a landfill and hog farm and areas had been stripped of topsoil.

NOW: Additional purchases through the years have added to the size and diversity of Possum Creek MetroPark. Thanks to proper land stewardship, Possum Creek MetroPark today is home to one of the largest and most diverse planted prairies in Ohio.

Five Rivers MetroParks continues to purchase land to protect and transform into future MetroParks. The Great Miami Mitigation Bank Conservation Area in Trotwood, created in 2011, is a prime example. This 540-acre farm was originally slated to be a landfill. Today, however, the first phase of its transformation is complete: It’s functioning as a wetland, thoursands of trees have been planted and it’s teeming with wildlife — including some birds rarely seen in the area. Plans call for the conservation area, adjacent to Sycamore State Park, to one day become Spring Run MetroPark.

Another site with potential to become a future MetroPark is Medlar Conservation Area. This former farmland, located near Austin Landing, is being converted to a second-growth forest and wetlands. MetroParks installed a paved recreation trail, located to protect the land’s most sensitive natural areas while giving visitors access to its most scenic ones. The Great-Little Trail is part of the nation’s largest paved trail network, with more than 340 miles to explore.

1972

THEN: Cox Arboretum joined the park district. Previously, the arboretum was managed by The James M. Cox, Jr., Arboretum Foundation, formed when a group of local conservationists convinced James M. Cox Jr. to donate his farm in the early ’60s.

THEN: Cox Arboretum joined the park district. Previously, the arboretum was managed by The James M. Cox, Jr., Arboretum Foundation, formed when a group of local conservationists convinced James M. Cox Jr. to donate his farm in the early ’60s.

NOW: The James M. Cox, Jr., Arboretum Foundation continues to support its popular namesake MetroPark. The Wegerzyn Gardens Foundation and the Friends of Carriage Hill also were formed to support specific parks. In 2014, the Five Rivers MetroParks Foundation was formed to secure philanthropic funding that supports the mission of Five Rivers MetroParks and all its work, including conservation activities.

1977

THEN: Aullwood Garden was added to the park district when local conservation supporter Marie Aull donated her home and 30-acre garden. Aull was instrumental in training staff in the nuances of estate gardening.

NOW: MetroParks includes a number of gardens where people can find inspiration. Staff teach gardening programs year-round, many of them focused on conservation principles such as using native plants to attract pollinators and composting.

1985

THEN: Five Rivers MetroParks launches a formal land stewardship program and hires staff focused on active management of natural areas.

NOW: MetroParks’ parks and conservation team conducts an integrated system of controlled succession, invasive plant management, wildlife management and restoration projects based on habitat management plans and biological surveys for each Five Rivers MetroParks location.

1986

THEN: Fort Carlisle, now Twin Creek MetroPark, was purchased.

NOW: Through the years, MetroParks has purchased 300 acres of scenic land in the Twin Creek Valley, located near Twin Creek and Germantown MetroParks. Another 250 acres in the area are protected through conservation easements, partnerships with local land owners that allow MetroParks to stretch its dollars. This large tract of natural area in the Twin Creek Valley gives MetroParks more reach in protecting green spaces and habitat. The area also is home to the 22-mile Twin Valley Backpacking Trail, and the rugged beauty of the area allows visitors to have wilderness experiences in Montgomery County similar to those found in national parks.

1990

THEN: As part of the its growing focus on rivers, Eastwood Park along the Mad River became part of the park district. Eastwood Lake was added in 1992.

NOW: Five Rivers MetroParks continues to focus on the rivers that are its namesake. In recognition of the rivers’ potential for economic development, MetroParks is working with community partners to develop the Dayton Riverfront Plan. Visit daytonriverfrontplan.org for more information.

1995

The name of the park district was changed to Five Rivers MetroParks to reflect a new commitment to the protection of greenspace and waterways. The new name referred to Montgomery County’s five waterways (the Great Miami, Stillwater and Mad rivers and Twin and Wolf creeks) and the importance of river corridors — areas that remain key to MetroParks’ conservation efforts.

2001

THEN: RiverScape MetroPark opened along the Great Miami River in downtown Dayton.

Five Rivers MetroParks introduced the idea of protecting land through conservation easements, partnerships with landowners that help protect land from development while stretching MetroParks’ funds.

NOW: RiverScape MetroPark continues to be an economic development driver in downtown Dayton and a place for our community to gather. New in-river features, RiverScape River Run, activate our rivers for experiences like whitewater paddling and fishing.

MetroParks helps protect more than 3,000 acres of land held in conservation easements.

2003

THEN: MetroParks purchased land that will become Woodman Fen. This ancient wetland dates to the last Ice Age 13,000 years ago.

NOW: After an extensive restoration funded through a private-public partnership, Woodman Fen showcases a unique habitat not found anywhere else in Montgomery County.

2007

THEN: Five Rivers MetroParks launched an outdoor recreation program. The first recreation-based event, GearFest, was held at the 2nd Street Market. During the next few years, MetroParks opened outdoor recreation facilities that incorporate conservation principles, such as the fully sustainable trails at the MetroParks Mountain Biking Area (MoMBA).

NOW: GearFest has become the Wagner Subaru Outdoor Experience, or OutdoorX, which has become the region’s premier outdoor recreation festival. MetroParks operates an ongoing sustainable trail initiative to renovate trails so they have less impact on the land, connect people to some of the most incredible natural areas and views within the park system, and help people have healthy, active lifestyles.

2009

THEN: Five Rivers MetroParks takes over management of the 2nd Street Market in downtown Dayton to strengthen the connection between the Market and MetroParks’ conservation mission.

NOW: The Market continues to be an economic development driver for downtown Dayton while improving access to fresh, local food and helping people have healthy, active lifestyles. The Market also accepts EBT benefits and Produce Perks, helping address food insecurity in our community.

2011

THEN: Five Rivers MetroParks began a community-driven reforestation project, Go Nuts!, in response to the threat of the emerald ash borer. Community volunteers collected nuts and seeds to help MetroParks grow new hickories and oaks — sometimes dropping off large garbage bags of what they’d gathered — and helped plant tree seedlings.

NOW: Reforestation continues to be an important conservation effort at MetroParks, and volunteers continue to be a tremendous help. MetroParks also grows seeds at the Barbara Cox Center for Sustainable Horticulture located at Cox Arboretum MetroPark, which now is the hub for reforestation efforts. Seeds are collected, germinated and grown into tree seedlings at the center. To participate in this year’s Go Nuts efforts, contact Yvonne Dunphe at 937-275-PARK or yvonne.dunphe@metroparks.org.

2015

THEN: Huffman Prairie State Natural Landmark was upgraded with new interpretive signage, making this historical site adjacent to the flying field where the Wright brothers tested their airplanes more accessible to the public.

NOW: Five Rivers MetroParks has partnered with Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to restore and manage Huffman Prairie since 1988. Thanks to these conservation efforts, many rare plants, birds and insects now can be found at the 112-acre prairie — one of the largest prairie remnants in Ohio. More information is at metroparks.org/huffmanprairie.

2018

Five Rivers MetroParks is creating a wetland and trail at a new pollinator prairie at Germantown MetroPark.

Five Rivers MetroParks is creating a wetland and trail at a new pollinator prairie at Germantown MetroPark.

The prairie was planted three years ago on 112 acres of former farmland using species from the Ohio Prairie Seed Nursery, also located at Germantown and managed by Five Rivers MetroParks. The prairie was created using seeds of native plants attractive to pollinators — such as milkweed, the only plant on which monarchs lay their eggs.

Already, the pollinator prairie is in full bloom and buzzing with insects, birds and other wildlife.

“When you stand in the prairie, you can hear red tail hawks, locusts, Carolina wrens, and field and song sparrows,” conservation manager Mary Klunk said. “The prairie is full of life. You can see monarchs, black and tiger swallowtails, native bees and wasps, rabbits, and deer. Short-eared owls have wintered there, and we’ve seen signs of barred owls, coyotes and fox.”

The new wetland will complement this wildlife array and create habitat for such species as dragonflies, Virginia Rail and a variety of frogs. MetroParks staff started building the wetland this past summer, using a series of levees to back up water. Staff assisted from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which helped fund the pollinator prairie project since protecting the dwindling monarch population is one of its priorities.

Once completed, the new trail — a stacked loop with half-mile and one-mile routes — will allow people to explore the pollinator prairie, wetland and nearby woodlands. Located off Boomershine Road, the site will be a convenient place for MetroParks education staff to host field trips and other programs that teach people about biodiversity, as several habitats can be viewed in a compact area with an easily accessible trail.

In addition to its work at the pollinator prairie, MetroParks is updating the Ohio Prairie Seed Nursery, which opened in 1988. Plans include revamping garden beds and growing new species of native plants.

During the past 30 years, the nursery has helped MetroParks staff plant and restore nearly 1,000 acres of prairie — the equivalent of almost 760 football fields.

“The science behind prairie restoration is evolving and, after three decades, it’s time to build on our work,” Klunk said. “We’ve had more than 30 years of observing prairie restoration to see how those prairies are responding and which plants are growing and which ones are meeting our biodiversity goals.”

MetroParks first began restoring prairies in the early ’80s. According to the National Parks Service, the prairies of North America once covered 200 million acres and supported myriad wildlife. With less than one percent of this native habitat left, prairie restoration is critical to protecting our region’s natural heritage because it benefits the soil and provides a habitat for native wildlife, such as butterflies and birds — pollinators that are essential to protecting our environment.